Five+ Years of Running and Fitness, Part Two: Sitter's Knee and HIIT

In June 2017, I joined a fitness centre in order to focus on core-strengthening exercises to improve my running form and avoid knee pain.

By Ryan McGreal

Posted January 31, 2019 in Blog (Last Updated January 31, 2019)

Contents

| 1 | Knee Trouble | ||

| 2 | Sitter's Knee | ||

| 3 | Core Strength Needed | ||

| 4 | High-Intensity Interval Training | ||

I've been trying to write up my five-year summary for several months now, and the analysis seems to keep getting bigger faster than I can finish it. So in an attempt to break the impasse, I'm publishing this review in several parts rather than all at once. This is Part Two of a series that will review of the experiences, challenges, insights, frustrations and successes of the past year.

1 Knee Trouble ↑

Before I started running, I had trouble with my right knee. It would click painfully on stairs and I couldn't squat deeply. After I started running, I actually found that the problems mostly went away. It would still click on stairs, but not painfully.

In some ways, my knee became the canary in the coal mine: for example, it would start grumbling once my shoes passed around 800 kilometres of use or when I was running with poor form, for example when I got tired.

I started having more trouble with it during my training for my first marathon when my weekly distances crept past 60 kilometres. Fortunately, I've been able to get the situation under control and now rarely experience any pain.

2 Sitter's Knee ↑

So-called runner's knee - the medical name is patellofemoral pain syndrome or PFPS - is something of a blanket term for inflammation and pain where the kneecap sits on the thigh bone.

While conventional wisdom assumes it's caused by running (hence the nickname), the fact is that running merely triggers the symptoms - especially after significantly ramping up distance and/or intensity to which body is not accustomed.

The underlying cause is usually bad running form due to poor musculoskeletal fitness - specifically, tight hamstrings, weak glutes and quadriceps, and poor core strength leading to instability. Without a network of strong, well-functioning muscles throughout the kinetic chain, the knee tends to collapse inward during impact, leading to poor tracking of the kneecap and irritation of the cartilage that holds it in place.

These underlying muscular factors, in turn, are primarily caused by extended sitting, which leaves the hamstrings too tight and the quadriceps too weak to support good running form. (This is just one of the many reasons extended sitting is extremely bad for your health.)

This condition should really be called sitter's knee, not runner's knee!

Before I started running, I spent a decade and a half sitting all day at work (I'm a software programmer). In late 2014, after attending a health conference and learning more about the dangers of sitting, I transitioned to a standing desk. It took a month to get used to it and tweak the ergonomics, but I never looked back. Now I work upright rather than sitting, and in addition I try to keep moving as much as possible while I work.

When I analyzed my running form during and after my marathon training, I noticed that when I strike the ground with my right foot, my right hip would dip a bit, causing my right knee to buckle slightly inward. That, in turn, caused my kneecap to move off-track, causing irritation and soreness.

3 Core Strength Needed ↑

It seemed to me that I would get some real benefit from focusing on strengthening my core, glutes and thigh muscles to improve the tracking of my knee.

In June of 2017, I took the logical next step and joined a fitness centre: McMaster Innovation Park Fitness Facility, managed by the wonderful fitness trainer Maureen Graszat. I generally work out three times a week, focusing on fundamental movements and core strength: bicep curls, bent rows, squats, deadlifts, bench presses, shoulder presses, bench flyes, lunges, planks and so on.

As I've gradually gotten stronger, I have found that my knee no longer troubles me. In addition, my running economy and form have steadily improved: I find I can run farther and faster with less perceived effort.

4 High-Intensity Interval Training ↑

As my knee has gotten stronger and more reliable, another change I've made to my running program is that once or twice a week I do a half-hour of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on the dreadmill at the fitness centre.

HIIT involves ramping up to a level of aerobic intensity that repeatedly raises your heart rate up to 80-90 percent of your maximum heart rate (calculated as 220 minus your age) for a short time, then lowers the intensity for a short break before going back to the higher intensity.

My maximum heart rate is 220 - 45 = 185, so my HIIT target heart rate is in the 150 to 167 beats per minute range (80-90 percent of 185).

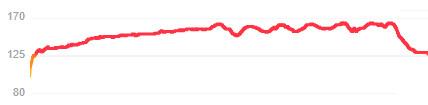

Here's a recent run in which I warmed up at around 11.25 km/h (7 mph), then alternated between bouts of 60 seconds at 14.5 km/h (9 mph) and 90 seconds at 12.5 km/h. You can see the oscillation in my heart rate in this chart from Fitbit:

Chart: heart rate during 30 minute HIIT on the dreadmill

An important measure of fitness is something called VO2 Max: it's the maximum rate at which your muscles can utilize oxygen while exercising. While the ultimate peak potential for your VO2 Max is determined by genetics, your performance within that potential range at any given point is largely a function of your fitness training, and HIIT is a highly effective way of increasing your fitness.

This stuff really matters: a higher VO2 Max predicts a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, all-risk mortality and specific mortality for certain types of cancer. And of course, a lower VO2 Max predicts a higher risk of all these things.

A higher VO2 Max also means running feels easier at any given pace, so there's a practical near-term benefit as well.

Fitbit calculates something that it calls a Cardio Fitness Level, which is a rough proxy for VO2 max. According to my profile, I have a Cardio Fitness Level of 46, which the app describes as "Very Good for men your age".

Still, knowing that there is an "Excellent" level beyond where I am today makes me feel a competitive drive to improve, hence my willingness to embrace HIIT.