A Fourth Year of Running: The Victory Lap that Wasn't

After completing my first marathon, I found myself caught in the grip of a kind of running ennui that has sapped my enthusiasm.

By Ryan McGreal.

3756 words. Approximately a 12 to 25 minute read.

Posted November 01, 2017 in Blog.

(Last Updated November 06, 2017)

Contents

| 1 | Reaching a Milestone | ||

| 2 | Unexpected Ennui | ||

| 3 | Road2Hope Half Marathon | ||

| 4 | Some More Good News | ||

| 5 | A Theory of Fitness | ||

| 6 | Breaking the Injury Cycle | ||

| 7 | Summary | ||

1 Reaching a Milestone ↑

Arriving at one goal is the starting point to another.

-- John Dewey

Except when it's not.

I began my fourth year of running feeling self-congratulatory (never a good sign). I had gone through an entire year without any debilitating injuries, and it felt like I finally understood my body well enough to train effectively within its operational tolerances. I was going from strength to strength and had embarked on an ambitious four-month training schedule to complete my first full marathon. I even managed to course-correct and ride out an incipient overtraining rut, but that turned out to be a warning sign of things to come.

I've already written about running my first marathon and won't rehash the entire experience here, but I've been struggling to make sense of its aftermath in the year since then.

Running down the Red Hill Valley Parkway

Running a marathon is easily the most difficult challenge - physically and mentally - I have ever undertaken, and while I managed to complete it in a respectable time (4:00:50 chip time), the more I think about it the more Pyrrhic that victory feels.

From the first time I shuffled out of the house on July 27, 2013 to shamble through a slow, clumsy 2.71 kilometre walk-run, I've always been able to keep my focus on the next goal. That next goal has always been achievable with time and effort: running continuously without a walk break, running five full kilometres, running six kilometres, running eight kilometres, running ten kilometres, averaging six minutes per kilometre (ten kilometres per hour), and so on an so on, all the way up to a marathon.

But training for the marathon required so much training that running started to feel like a grind instead of a joy. The marathon itself was unbelievably gruelling. I managed to get through it but just barely. When it was done I could scarcely imagine running another marathon, let alone taking on something even longer.

This was a new feeling for me. Each previous milestone had left me excited to turn my sights to the next one. It was after finishing the 2016 Around the Bay race, for example, that I solidified my commitment to tackle a marathon next. I finished the marathon, but it felt more like the marathon finished me!

2 Unexpected Ennui ↑

Ce sont justement cette repugnance, cet ennui qu'il convient de developper en nous, afin de nous demarquer de l'espece.

-- Michel Houellebecq

I gradually recovered physically in the weeks that followed the marathon and resumed my usual baseline regimen, but I was caught in the grip of a kind of running ennui that sapped my enthusiasm.

Running across the Chedoke Rail Trail Highway 403 overpass

I was able to maintain my weekday runs, but on the weekends I increasingly found myself succumbing to a myriad of excuses to blow off my long run. The excuses had not gotten any better, I had merely become more susceptible to them.

As every distance runner knows, the long run is the foundation of endurance and fitness. It builds up cardiovascular and aerobic capacity, increases cellular mitochondria, trains muscles to burn fat for fuel, and bolsters psychological toughness. It is the essential base on which your entire running program rests.

Traditionally, the long run had been one of the physical, emotional and philosophical highlights of my entire week - a glorious extended mindfulness meditation that placed me squarely in the universe and left me feeling euphoric. And yet as often as not, I found myself unable to drag my ass out of bed to do it.

It was as if, having at last become free of exogenous challenges, I was finally turning against myself. Or to frame it differently, without an external goal I no longer knew what to run for. (Such is the depth of my funk that this annual review is already three months late.)

Tiffany Falls

After a winter of half-assing my long runs, I ran the 30 kilometre Around the Bay Road Race on March 26, 2017 and managed to shave two and a half minutes off my finishing time from the previous year - but it was obvious to me that I was freeloading on my residual aerobic base instead of maintaining or building on it.

| 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bib | 228 | 4296 |

| Guntime | 2:54:45 | 2:53:30 |

| Chiptime | 2:52:32 | 2:50:03 |

| Overall Place | 2254/5259 | 1836/4244 |

| Overall Percentile | 43% | 43% |

| Gender Place (M) | 1509/2669 | 1247/2224 |

| Gender Percentile | 57% | 56% |

| Age Place (M40-44) | 267/443 | 201/327 |

| Age Percentile | 60% | 61% |

Aside from Around the Bay, I suddenly had no motivation to sign up for races. I missed both the Unity Run and the Sulphur Springs Trail Race (it was already sold out when I went to sign up for it). After a summer of futzing around, I was at the point where I wasn't even sure I'd be able to complete the Road2Hope half marathon on Sunday, November 6, 2017.

I have not yet figured out how I am going to work through this malaise. Perhaps it will involve setting new goals, or reframing my expectations. Maybe I need to focus on improving my general fitness to the point where I can run a marathon without feeling destroyed at the end. I have to say that just writing this down has helped to improve my mood.

3 Road2Hope Half Marathon ↑

As it turns out, I had a really strong race in the Road2Hope half marathon. It was one of those races where everything goes well, I had lots of energy, my form felt good and The clocks went back on Saturday night so I got an extra hour of sleep, and I woke up feeling good. I followed my usual race-day legal performance-enhancing regimen: whole grain toast with nut and seed butter for breakfast, a prophylactic ibuprofen and a big mug of coffee.

The temperature was mild but rainy, and the half-marathon began with blatting cold rain coming in sideways. It's always a crapshoot trying to figure out what to wear, and I ended up heading out in shorts and a long-sleeve shirt without a windbreaker. It was unpleasant for the first several minutes but once I warmed up it felt fine. By the time I reached around six or seven kilometres in, I had already rolled up my sleeves.

The Road2Hope half marathon feels a bit like cheating, especially after last year: it has all of the highlights of the full marathon, including an exhilarating run down the Red Hill Valley Parkway and that delicious bowl of vegetable soup at the end, but over a total distance that you can still pull off after a half-assed training regimen.

Once the starting line logjam cleared and we started to spread out, I settled into a fast pace that I assumed I probably would not be able to maintain for the full distance. I made up some additional time on the Red Hill, gambling that I wouldn't be too gassed for the shorter final stretch along the Waterfront Trail. Surprisingly, I didn't run out of energy and was able to sustain the pace right through the end.

| Bib | 784 |

|---|---|

| Guntime | 1:54:20 |

| Chiptime | 1:53:20 |

| Overall Place | 496/1326 |

| Overall Percentile | 37% |

| Gender Place (M) | 323/613 |

| Gender Percentile | 53% |

| Age Place (M40-44) | 48/82 |

| Age Percentile | 59% |

I completed the race with a guntime (from when the gun goes off until I crossed the finish line) of 1:54:20 and a chiptime (from when I crossed the starting line until I crossed the finish line) of 1:53:20. I came in 496th place out of 1,326 total finishers, and in 323rd place out of 613 male finishers. I was in 48th place among 82 males age 40-44. According to Runkeeper, I had an average speed of 11.21 km/h or 5:21 minutes/km.

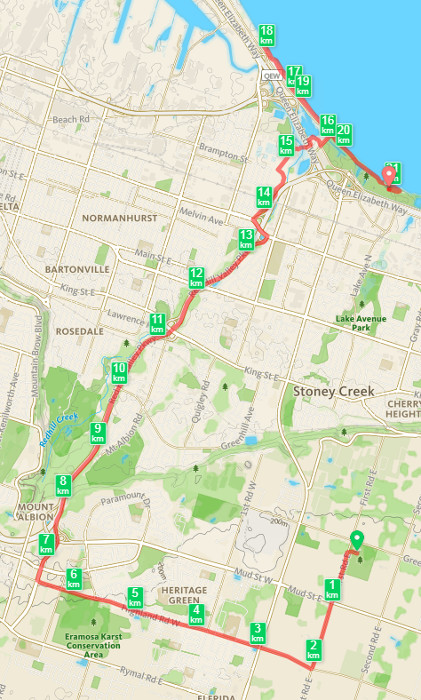

Road2Hope 2017 Half-Marathon route map from Runkeeper

Of course, it puts things into perspective to finish a half-marathon at your personal best pace, only to have the first-place runner in the *full* marathon finish soon after you. Toronto's Bonsa Gonfa, following a police motorcycle escort through the assorted half-marathoners, finished his 42.195 kilometres in a very impressive 2:23:33.

Road2Hope 2017 Marathon first place finisher Bonsa Gonfa just before the finish line

4 Some More Good News ↑

The bad news is nothing lasts forever.

The good news is nothing lasts forever.

-- J. Cole

So my running situation is not all doom and gloom. When I do manage to eke out a long run, they're in the 18-20 kilometre range, and I'm still maintaining 30-40 kilometres in distance a week, even on weeks when I 'miss' my long run.

I've also managed to maintain what feels like a good, sustainable running form, even though I'd like to increase my cadence from 170 steps per minute toward 180 steps per minute. I definitely need to get back in the game, but at least I'm not starting from scratch.

In addition, this past June I finally took got my act together and committed to joining the McMaster Innovation Park Fitness Facility to incorporate regular weight lifting into my routine. Notwithstanding illness, I go three times a week and follow a program tailored for runners that was helpfully provided by Maureen, the MIP gym's amazing fitness coordinator.

I've long put off joining a gym because I wasn't sure how to fit it into my schedule and I always assumed I would hate everything about it, but my experience has been way better than I expected. The facility is well-appointed and not too busy, the 'culture' is respectful and accepting without any hardbody showoffs, and the weight lifting itself is a lot more rewarding than I thought it would be. There's something pretty awesome about the visceral feeling of growing physically stronger over time.

Perhaps most important, I've gone another year and then some without any debilitating injuries. I think I've finally figured out a theory of fitness and injury prevention that works for me. Which is to say, I haven't come up with a new theory, I've just finally gotten my head around how to apply this common sense to my own training.

Footsteps in the snow

5 A Theory of Fitness ↑

What does not kill us makes us stronger.

- Friedrich Nietzsche

Of course, Nietzsche's famous ode to hormesis is not quite correct. Some things that don't kill us nevertheless manage to make us weaker and more prone to further infirmity. I've learned that mapping the distinction between those trials that strengthen us and those trials that weaken us is at the heart of successful endurance running.

We might turn to Nassim Nicholas Taleb to help us think more clearly about the matter. In 2012, Taleb published a brilliant and often unbearably smug masterpiece of trolling-as-high-art called Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. (Reading it, my reaction was split almost evenly between rank admiration and a burning desire to hurl the book across the room.)

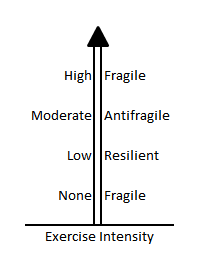

Taleb's genius is in recognizing that the traditional conceptual dichotomy of resilience vs. fragility is actually a truncated view of a broader spectrum.

We say something is resilient or robust if it can withstand stress, and fragile or brittle if it cannot withstand stress. Taleb articulated another quality: we can say something is antifragile if it not only withstands stress but also becomes stronger from it.

Running up the Bruce Trail switchback between Filman Road and Wilson Street

The concept of antifragility can help us think more clearly about exercise, stress and fitness. Physical exercise, after all, is a stressor, and a body exercising is a body being subjected to acute stress.

The intersection between the state of a body and the intensity of the stress will determine whether the experience is one of fragility, resilience or antifragility.

Without physical exercise, the human body gradually becomes fragile. Muscles atrophy, bones weaken, aerobic capacity declines, and the body's capacity to withstand any kind of stress (including emotional) deteriorates.

A body subjected to a baseline level of exercise to maintains current fitness is experiencing resilience. It can withstand moderate stress and disorder, but does not become stronger as a result of the exercise.

A body subjected to more vigorous exercise that is intense enough to increase fitness is experiencing antifragiity. A sustained program of progressively more demanding physical exercise that pushes the body slightly beyond its baseline level of performance, followed by adequate rest and recovery, produces chronic adaptations that render the body progressively stronger. These adaptations to a steadily increasing exercise workload are cumulative: your baseline fitness level steps up with each cycle of exercise-and-recovery.

However, a body subjected to overtraining, i.e. pushing too fast and/or too far without adequate recovery time, once again experiences fragilty. When you exercise, your body tissues undergo damage - torn muscle fibres, microscopic bone fractures, and so on. This is why recovery time is essential: during this time, your body repairs the damage and leaves your muscles and bones slightly thicker and stronger than before.

If you exercise repeatedly without giving your body time to recover, you start accumulating damage. Progressive adaptation stalls, fitness starts to decline, and the risk of injury goes up. Tiny muscle tears can coalesce into a major tear; or microscopic bone damages can coalesce into a stress fracture.

Likewise, if you exercise at an intensity that is far higher than that to which your body is accustomed, you may overstress it and cause an injury.

Chart: spectrum of exercise intensity and body response

6 Breaking the Injury Cycle ↑

The more injuries you get, the smarter you get.

-- Mikhail Baryshnikov

It was by applying this principle over the past two years - intuitively at first and more formally as the concept has become more clear - that I have managed to break out of the overuse-injury-every-few-months cycle I was in during my first two years of running.

This was particularly vital during my marathon training, when I pushed my total weekly running distance into previously uncharted territory. At one point I found myself getting into an incipient overtraining rut where I was feeling constant fatigue, started craving junky carbs and could feel my right knee starting to twinge.

I managed to recognize what was going on before it was too late. I immediately backed away from the overtraining threshold, reduced my intensity and focused on cleaning up my form. Once I was back ahead of the curve, I was able to resume my incremental trajectory instead of spiralling into a hole or straight-up injuring something.

Indeed, my right knee has somewhat taken on the role of the canary in my body's coal mine. Before I started running, it used to click loudly and sometimes painfully on stairs. After I started running, it quickly stopped bothering me and would only twinge when my shoes would wear out, around 800 kilometres total distance.

It started to bug me a bit more persistently during my marathon training, and it has never entirely gone away in the year since then. I've noticed that it twinges in certain specific circumstances: when I'm going too fast, when I have sloppy form, when my cadence gets too low (significantly lower than 170 steps per minute), when I get tired at the end of a long run, and of course when my shoes are worn out.

I've tried to focus on strengthening my knees as part of my workouts at the gym, incorporating squats and lunges to build muscle strength so there is less stress on the bones, tendons, ligaments, fascia and other connective tissues. That seems to be helping, and my knee rarely causes problems - but I'm conscious that it's there, waiting quietly to fail if I let my guard down.

Running on the Ravine Road Trail

7 Summary ↑

All in all, the past year can most charitably be considered a maintenance year in my running career. After the high water mark of last November's marathon, I have mostly coasted for the rest of the year, leading to a year-end summary in which my overall distance was down slightly from my third year while my average speed was modestly higher.

That said, my annualized distance is down significantly for the first three months of my fifth year, while my average speed is holding steady.

| Year | Distance (km) | Calories | Speed (km/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,325.21 | 155,468 | 9.25 |

| 2 | 1,463.20 | 149,437 | 9.50 |

| 3 | 2,528.96 | 243,252 | 10.27 |

| 4 | 2,434.37 | 223,817 | 10.56 |

| 5 YTD | 475.46 | 43,110 | 10.56 |

| Total | 8,227.20 | 815,084 |

It's pretty amazing how the total distance adds up when you keep running week after week. The 8,227 kilometres I've run since July 27, 2013 are enough to take me from St. John's, Newfoundland clear across to Vancouver, British Columbia (by road, not as the crow flies) with another 766 kilometres to spare - enough to turn around and backtrack into Yoho National Park, just outside of Banff. Looked at differently, it's just over one-fifth of the distance around the entire planet.

Deer in Dundas Valley

Likewise, I've been tracking my daily steps since October 23, 2014, and in that time I have taken a hard-to-get-my-head-around total of 24,845,396 steps. That works out to an average of 22,485 steps a day over the past three years.

Finally, as I proceed through my fifth year of running, I'm conscious of the fact that among North Americans who undertake efforts to lose weight, the chance of succeeding in maintaining weight loss over five years is a dispiriting five percent. The other 95 percent regain all the lost weight and then some.

While I continue to struggle with a lingering squishiness around my middle, I have so far managed to stay ahead of some pretty long odds - despite being caught in a bit of a fitness tailspin over the past year. That is something to be grateful for (and probably worth its own article in the future).

Running has improved my quality of life immeasurably, and I hope to be able to report in my next dispatch that I have managed to find a way through this extended funk and emerge on the other side with a renewed and sustained passion.

Running on the Escarpment Rail Trail

More Reading: